18th Century apparel / First hand

accounts

from

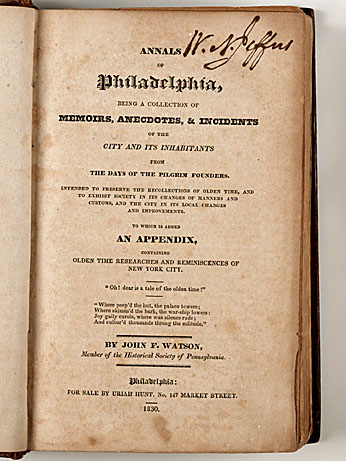

The Annals of

Philadelphia

by

John F. Watson

Pub.1830

Here follows the text from the

chapter "Apparel" from this excellent old book.

I hope you find it interesting as

well as helpful

" We run through every

change, which fancy

At the loom has genius to

supply."

" We run through every

change, which fancy

At the loom has genius to

supply."

THERE is a very marked and wide difference between our

moderns and the ancients in their several views of appropriate

dress: The latter, in our judgment of them, were always stiff

and formal, unchanging in their cut and fit in the gentry, or

negligent and rough in texture in the commonalty; whereas the

moderns, casting off all former modes and forms, and inventing

every new device which fancy can supply, just please the wearers

"while the fashion is at full."

It will much help our just conceptions of our forefathers, and

their good dames, to know what were their personal appearances:

To this end, some facts illustrative of their attire will be given.

Such as it was among the gentry, was a constrained and pains-

taking service, presenting nothing of ease and gracefulness in

the use. While we may wonder at its adoption and long contin-

uance, we will hope never again to see it return! But who can

hope to check or restrain fashion if it should chance-again to set

that way; or, who can foresee that the next generation may not be

even more stiff and formal than any which has past, since we see,

even now, our late graceful and easy habits of both sexes already

partially supplanted by "monstrous novelty and strange disguise!"

-men and women stiffly corsetted&emdash;another name for stays of

yore, long unnatural-looking waists, shoulders stuffed and deform-

ed as Richard's, and artificial hips- protruding garments of as

ample folds as claimed the ton when senseless hoops prevailed !

Our forefathers were excusable for their formal cut, since, know~

ing no changes in the mode, every child was like its sire, resting

in " the still of despotism," to which every mind by education and

habit was settled; but no such apology exists for us, who have wit-

nessed better things. We have been freed from their servitude;

and now to attempt to go back to their strange bondage, deserves

the severest lash of satire, and should be resisted by every satirist

and humorist who writes for public reform.

In all these things, however, we must be subject to female control;

for, reason as we will, and scout at monstrous novelties as we may,

female attractions will eventually win and seduce our sex to their

attachment, "as the loveliest of creation," in whatever form they

may choose to array: As " it is not good for man to be alone," they

will be sure to follow through every giddy maze which fashion

runs. We know, indeed, that ladies themselves are in bondage to

their milliners, and often submit to their new imported modes with

lively sense of dissatisfaction, even while they commit themselves

to the general current, and float along with the multitude.

OUR forefathers were occasionally fine practical satirists on

offensive innovations in dress&emdash;they lost no time in paraphrastic

verbiage which might or might not effect its aim, but with most

effective appeal to the populace, they quickly carried their point,

by making it the scoff and derision of the town! On one occasion,

when the ladies were going astray after a passion for long red

cloaks, to which their lords had no affections, they succeeded to

ruin their reputation, by concerting with the executioners to have

a female felon hung in a cloak of the best ton ! On another occa-

sion, in the time of the Revolution, when the " tower" head-gear

of the ladies were ascending, Babel-like, to the skies, the growing

enormity was effectually repressed, by the parade through the

streets of a tall male figure in ladies attire, decorated with the odi-

ous tower-gear; and preceded by a drum! At an earlier period,

one of the intended dresses, called a trollopee, (probably from the

word trollop) became a subject of offence. The satirists, who

guarded and framed the sumptuary code of the town, procured the

wife of Daniel Pettitteau the hangman, to be arrayed in full dress

trollopee, &c. and to parade the town with rude music ! Nothing

could stand the derision of the populace ! Delicacy and modesty

shrunk from the gaze and sneers of the multitude ! And the trollopee,

like the others, was abandoned !

Mr. B------, a gentleman of 80 years of age, hag given me his

recollections of the costumes of his early days in Philadelphia, to

this affect, to wit: Men wore three-square or cocked hats, and wigs,

coats with large cuffs, big skirts, lined and stiffened with buckram.

None ever saw a crown higher than the head. The coat of a beau

had three or four large plaits in the skirts, wadding almost like a

coverlet to keep them smooth, cuffs, very large, up to the elbows,

open below and inclined down, with lead therein; the capes were

thin and low, so as readily to expose the close plaited neck-stock

of fine linen cambric, and the large silver stock-buckle on the

back of the neck, shirts with hand ruffles, sleeves finely plaited,

breeches close fitted, with silver, stone or paste gem buckles, shoes

or pumps with silver buckles of various sizes and patterns, thread,

worsted and silk stockings; the poorer class wore sheep and buck-

skin breeches close set to the limbs. Gold and silver sleeve but-

tons, set with stones or paste, of various colours and kinds, adorned

the wrists of the shirts of all classes. The very boys often wore

wigs, and their dresses in general were similar to that of the men.

The odious use of wigs was never disturbed till after the return

of Braddock's broken army. They appeared in Philadelphia, wea-

ring only their natural hair&emdash;a mode well adapted to the military,

and thence adopted by our citizens. The king of England too,

about this time, having cast off his wig malgre the will of the peo-

ple, and the petitions and remonstrances of the periwig makers

of London, thus confirmed the change of fashion here, and com-

pleted the ruin of our wig makers.*

*The use of wigs must have been peculiarly an English fashion, as I find Kalm in 1749

speaks of the French gentlemen then as wearing their own hair.

The women wore caps, (a bare head was never seen !) stiff stays,

hoops from six inches to two feet on each side, so that a full

dressed lady entered a door like a crab, pointing her obtruding

flanks end foremost, high healed shoes of black stuff with white

cotton or thread stockings; and in the miry times of winter they

wore clogs, gala shoes, or pattens.

The days of stiff coats, sometimes wire-framed, and of large

hoops, was also stiff and formal in manners at set balls and

assemblages. The dances of that day among the politer class were

minuets, and some times country dances; among the lower order

hipsesaw was every thing.

As soon as the wigs were abandoned and the natural hair was

cherished, it became the mode to dress it by plaiting it, by queu-

ing and clubbing, or by wearing it in a black silk sack or bag,

adorned with a large black rose.

In time, the powder, with which wigs and the natural hair had

been severally adorned, was run into disrepute only about 28 to

30 years ago, by the then strange innovation of "Brutus heads ;"

not only then discarding the long cherished powder and perfume and

tortured frizzle-work, but also literally becoming " Round heads,"

by cropping off all the pendant graces of ties, bobs, clubs, queus, &c !

The hardy beaux who first encountered public opinion by appea-

ring abroad unpowdered and cropt, had many starers. The old

men for a time obstinately persisted in adherence to the old regime,

but death thinned their ranks, and use and prevalence of numbers at

length gave countenance to modern usage.

Another aged gentlemen, colonel M. states, of the recollections

of his youth, that young men of the highest fashion wore swords&emdash;

so frequent it was as to excite no surprise when seen. Men as old

as forty so arrayed themselves. They wore also gold laced cocked

hats, and similar lace on their scarlet vests. Their coat-skirts

were stiffened with wire or buckram and lapt each other at the

lower end in walking. In that day no man wore drawers, but

their breeches (so called unreservedly then) were lined in winter,

and were tightly fitted.

From various reminiscents we glean, that laced ruffles, depending

over the hand, was a mark of indispensable gentility. The coat

and breeches were generally desirable of the same material&emdash;of

"broad cloth" for winter, and of silk camlet for summer. No

kind of cotton fabrics were then in use or known; hose were there-

fore of thread or silk in summer, and of fine worsted in winter;

shoes were square-toed and were often " double channelled." To

these succeeded sharp toes as peaked as possible. When wigs were

universally worn, grey wigs were powdered, and for that purpose

sent in a paper box frequently to the barber to be dressed on his

block-head. But " brown wigs," so called, were exempted from

me white disguise. Coats of red cloth, even by boys, were consid-

erably worn, and plush breeches and plush vests of various

colours, shining and slipping, were in common use. Everlast-

ing, made of worsted, was a fabric of great use for breeches and

sometimes for vests. The vest had great depending pocket flaps,

and the breeches were very short above the stride, because the art

of suspending them by suspenders were unknown. It was then

the test of a well formed man, that he could by his natural form

readily keep his breeches above his hips, and his stockings, with

out gartering, above the calf of the leg. With the queus belonged-

frizled side locks, and toutpies formed of the natural hair, or, in

defect of a long tie, a splice was added to it. Such was the gene-

ral passion for the longest possible whip of hair, that sailors and

boat men, to make it grow, used to tie theirs in eel skins to aid its

growth. Nothing like surtouts were known; but they had coat-

ing or cloth great coats, or blue cloth and brown camlet cloaks,

with green baize lining to the latter. In the time of the American

war, many of the American officers introduced the use of Dutch

blankets for great coats. The sailors in the olden time used to

wear hats of glazed leather or of woollen thrumbs, called chapeaus,

closely woven and looking like a rough knap; and their " small

clothes,"as we would say now, were immense wide petticoat-breech-

es, wide open at the knees, and no longer. About 70 years ago

our working men in the country wore the same, having no fal-

ling flaps but slits in front; they were so full and free in girth, that

they ordinarily changed the rear to the front when the seat became

prematurely worn out In sailors and common people, big silver

broaches in the bosom were displayed, and long quartered shoes

with extreme big buckles on the extreme front.

Gentlemen in the olden time used to carry muffees in winter.

lt was in effect a little woollen muff of various colours, just big

enough to admit both hands, and long enough to screen the wrists

which were then more exposed than now; for they then wore short

sleeves to their coats purposely to display their fine linen and

plaited shirt sleeves, with their gold buttons and sometimes laced

ruffles. The sleeve cuffs were very wide, and hung down depressed

with leads in them.

In the summer season, men very often wore calico morning-

gowns at all times of the day and abroad in the streets. A dnmamask

banyan was much the same thing by another name. Poor labour-

ing men wore ticklenberg linen for shirts, and striped ticken breeches;

they wore grey duroy-coats in winter; men and boys always wore

leather breeches. Leather aprons were used by all tradesmen and

workmen.

Some of the peculiarities of the female dress was to the follow-

ing effect, to wit: Ancient ladies are still alive who have told me

that they often had their hair tortured for four hours at a sitting

in getting the proper crisped curls of a hair curler. Some who

desired to be inimitably captivating, not knowing they could be

sure of professional services where so many hours were occupied

upon one gay head, have actually had the operation performed

the day before it was required, then have slept all night in a sit-

ting posture to prevent the derangement of their frizle and curls !

This is a real fact, and we could, if questioned, name cases. They

were, of course, rare occurrences, proceeding from some extra occa-

sions, when there were several to serve, and but few such refined

hair dressers in the place.

This formidable head-work was succeeded by rollers over which

the hair was combed above the forehead. These again were super-

seded by cushions and artificial curled work, which could be sent

out to the barber's block, like a wig, to be dressed, leavinig the

lady at home to pursue other objects thus producing a grand re-

formation in the economy of time, and an exemption too from for-

mer durance vile. The dress of the day was not captivating to all,

as the following lines may show, viz.

Give Chioe a bushel of horse-hair and wool,

Of paste and pomatum a pound,

Ten yards of gay ribbon to deck her sweet skull,

And gauze to encompass it round.

Let her flags fly behind for a yard at the least,

Let her curls meet just under her chin,

Let these curls be supported, to keep up the jest,

With an hundred- instead of one pin.

Let her gown be tuck'd up to the hip on each side,

Shoes too high for to walk or to jump,

And to deck the sweet creature complete for a bride

Let the cork cutter make her a rump.

Thus finish'd in taste, while on Chloe you gaze,

You may take the dear charmer for life,

But never undress her&emdash;for, out of her stays,

You'll find you have lost half your wife !

When the ladies first began to lay off their cumbrous hoops they

supplied their place with successive succedaneums, such as these,

to wit: First came bishops -a thing stuffed or padded with horse

hair; then succeeded a smaller affair under the name of cue de

Paris, also padded with horse hair ! How it abates our admiration

to contemplate the lovely sex as bearing a roll of horse hair under

their garments! Next they supplied their place with silk or cali-

manco, or russell thickly quilted and inlaid with wool, made into

petticoats; then these were supplanted by a substitute of half a

dozen of petticoats. No wonder such ladies needed fans in a sultry

summer, and at a time when parasols wore unknown, to keep off

the solar rays ! I knew a lady going to a gala party who had so

large a hoop that when she sat in the chaise she so filled it up, that

the person who drove it (it had no top) stood up behind the box

and directed the reins !

Some of those ancient belles, who thus sweltered under the weight

of six petticoats, have lived now to see their posterity, not long

since, go so thin and transparent, a la Francaise, especially when

between the beholder and a declining sun, as to make a modest

eye sometimes instinctively avert its gaze !

Among some other articles of female wear we may name the

following, to wit: Once they wore a " skimmer hat," made of a

fabric which shone like silver tinsel; it was of a very small flat

crown and big brim, not unlike the present Leghorn flats. Another

hat, not unlike it in shape, was made of woven horse hair, wove in

flowers, and called " horse-hair bonnets,"&emdash;an article which might

be again usefully introduced for children's wear as an enduring

hat for long service. I have seen what was called a bath-bonnet,

made of black satin, and so constructed to lay in folds that it

could be set upon like a chapeau bras,&emdash;a good article now for

travelling ladies! "The mush-mellon" bonnet, used before the

Revolution, had numerous whale-bone stiffeners in the crown, set

at an inch apart in parallel lines and presenting ridges to the eye,

between the bones. The next bonnet was the " whale-bone bonnet,"

having only the bones in the front as stiffeners. " A calash bonnet"

was always formed of green silk; it was worn abroad, covering

the head, but when in rooms it could fall back in folds like the

springs of a calash or gig top: to keep it up over the head it was

drawn up by a cord always held in the hand of the wearer. The

" wagon bonnet," always of black silk, was an article exclusively

in use among the Friends, was deemed to look, on the head, not

unlike the top of the Jersey wagons, and having a pendent piece

of like silk hanging from the bonnet and covering the shoulders.

The only straw wear was that called the " straw beehive bonnet,"

worn generally by old people.

The ladies once wore " hollow breasted stays," which were ex-

ploded as injurious to the health. Then came the use of straight

stays. Even little girls wore such stays. At one time the gowns

worn had no fronts; the design was to display a finely quilted

Marseilles, silk or satin petticoat, and a worked stomacher on the

waist. In other dresses a white apron was the mode; all wore

large pockets under their gowns. Among the caps was the "queen's

night cap,"&emdash;the same always worn by Lady Washington. The

"cushion head dress" was of gauze stiffened out in cylindrical

form with white spiral wire. The border of the cap was called

the balcony.

A lady of my acquaintance thus describes the recollections of

her early days preceding the war of Independence. Dress was

discriminative and appropriate, both as regarded the season and

the character of the wearer. Ladies never wore the same dresses

at work and on visits; they sat at home, or went out in the morn-

ing, in chints; brocades, satins and mantuas were reserved for

evening or dinner parties. Robes or negligees, as they were

called, were always worn in full dress. Muslins were not worn

at all. Little Misses at a dancing-school ball (for these were al-

most the only feates that fell to their share in the days of discrimi

nation) were dressed in frocks of lawn or cambric. Worsted

was then thought dress enough for common days.

As a universal fact, it may be remarked that no other colour

than black was ever made for ladies bonnets when formed of silk

or satin. Fancy colours were unknown, and white bonnets of silk

fabric had never been seen. The first innovation remembered, was

the bringing in of blue bonnets.

The time was, when the plainest women among the Friends

(now so averse to fancy colours) wore their coloured silk aprons,

say, of green, blue, &c. This was at a time when the gay wore

white aprons. In time white aprons were disused by the gentry,

and then the Friends left off their coloured ones and used the

white ! The same old ladies, among Friends whom we can remem-

ber as wearers of the white aprons, wore also large white beaver

hats, with scarcely the sign of a crown, and which was indeed con-

fined to the head by silk cords tied under the chin. Eight dollars

would buy such a hat, when beaver fur was more plentiful. They

lasted such ladies almost a whole life of wear. They showed no fur.

Very decent women went abroad and to churches with check

aprons. I have seen those, who kept their coach in my time to

bear them to church, who told me they went on foot with a check

apron to the Arch street Presbyterian meeting in their youth.

Then all hired women wore short-gowns and petticoats of domestic

fabric, and could be instantly known as such whenever seen abroad.

In the former days it was not uncommon to see aged persons

with large silver buttons to their coats and vests&emdash;it was a mark

of wealth. Some had the initials of their names engraved on each

button. Sometimes they were made out of real quarter dollars,

with the coinage impression still retained,&emdash;these were used for

the coats, and the eleven-penny-bits for vests and breeches. My

father wore an entire suit decorated with conch-shell buttons,

silver mounted.

An aged gentleman O. J. Esq. told me of seeing one of the most

respectable gentlemen going to the ball room in Lodge alley in an

entire suit of drab cloth richly laced with silver.

On the subject of wigs, I have noticed the following special facts,

to wit: They were as generally worn by genteel Friends as by

any other people. This was the more surprising as they religiously

professed to exclude all superfluities and yet nothing could have

been offered to the mind as so essentially useless.*

*The Friends have, however, a work in their library, written against perukes and

their makers, by John Mulliner.

In the year 1685, William Penn writes to his steward, James

Harrison, requesting him to allow the Governor, Lloyd, his depu-

ty, the use of his wigs in his absence.

In the year 1719, Jonathan Dickinson, a Friend, in writing to

London for his clothes, says. " I want for myself and my three

sons each a wigg&emdash;light good bobbs."

In 173O, I see a public advertisement to this effect in the Gazette,

to wit: " A good price will be given for good clean white horse-

hair, by Wilham Crassthwaite, peruke maker." Thus showing

of what materials our forefathers got their white wigs !

In 1737, the perukes of the day as then sold, were thus described,

to wit: "Tyes, bobs, majors, spencers, fox-tails and twists, together

with curls or tates (tetes) for the ladies."

In the year 1765, another peruke maker advertises prepared

hair for judges' full bottomed wigs, tyes for gentlemen of the bar

to wear over their hair, brigadiers, dress bobs, bags, cues, scratches,

cut wigs, &c. and to accommodate ladies he has tates, (tetes) towers,

&c. At same time a stay maker advertises cork stays, whale-bone

stays, jumps, and easy caushets, thin boned Misses' and ladies'

stays, and pack thread stays !

Some of the advertisements of the olden time present some curi-

ous descriptions of masquerade attire, such as these, viz:

Year 1722&emdash;Run away from the Rev. D. Magill, a servant

clothed with damask breeches and vest, black broad-cloth vest,

a broad-cloth coat, of copper colour, lined and trimmed with

black, and wearing black stockings ! Another servant is descri-

bed as wearing leather breeches and glass buttons, black stockings,

and a wig !

In l724, a run-away barber is thus dressed, viz:&emdash;wore a light

wig, a grey kersey jacket lined with blue, a light pair of drugget

breeches, black roll-up stockings, square toed shoes, a red leath-

ern apron. He had also a white vest and yellow buttons, with

red linings !

Another run-away servant is described as wearing "a light

short wig," aged 20 years; his vest white with yellow buttons and

faced with red !

A poetic effusion of a lady, of 1725, describing her paramour,

thus designates the dress which most seizes upon her admiration as

ball guest:

"Mine, a tall youth shall at a ball be seen

Whose legs are like the spring, all cloth'd in green:

A yellow riband ties his long cravat,

And a large knot of yellow cocks his hat !"

We have even an insight into the wardrobe of Benjamin Frank-

lin in the year 1738, caused by his advertisement for stolen

clothes, to wit: " broad-cloth breeches lined with leather, sagathee

coat lined with silk, and fine homespun linen shirts."

From one advertisement of the year 1745, I take the following

now unintelligible articles of dress-all of them presented for sale

too, even for the ladies, on Fishbourne's wharf, " back of Mrs. Fish-

bourne's dwelling," to wit: "Tandems, isinshams, nuns, bag and

gulix, (these all mean shirting) huckabacks, (a figured worsted

for women's gowns) quilted humhums, turkettees, grassetts, single

allopeens, children's stays, jumps and bodice, whalebone and iron

busks, men's new market caps, silk and worsted wove patterns for

breeches, allibanies, dickmansoy, cushloes, chuckloes, cuttanees,

crimson dannador, chain'd soosees, lemonees, byrampauts, moree,

naffermamy, saxlingham, prunelloe, barragons, druggets,

florettas!" &c. &c.

A gentleman of Cheraw, South Carolina, has now in his posses-

sion an ancient cap, worn in the colony of New Netherlands

about 150 years ago, such as may have been worn by some of the

Chieftains among the Dutch rulers set over us. The crown is of

elegant yellowish brocade, the brim of crimson silk velvet, turned

up to the crown. It is elegant even now.

In the year 1749, I met with the incidental mention of a singu-

lar over-coat, worn by captain James as a storm coat, made entire-

Iy of beaver fur, wrought together in the manner of felting hats.

I have seen two fans, used as dress fans before the Revolution

which cost eight dollars a piece. They were of ivory frame and

pictured paper. What is curious in them is, that the sticks fold

up round as a cane.

Before the Revolution no hired men or women wore any shoes so

fine as calf skin; that kind was the exclusive property of the

gentry; the servants wore coarse neats-leather. The calf skin

shoe then had a white rand of sheep skin stitched into the top edge

of the sole, which they preserved white as a dress shoe as long as

possible.

It was very common for children and working women to wear

beads made of Job's-tears, a berry of a shrub. They used them

for economy, and said it prevented several diseases.

Until the period of the Revolution, every person who wore a fur

hat had it always of entire beaver. Every apprentice, at receiving

his "freedom," received a real beaver, at a cost of six dollars.

Their every-day hats were of wool, and called felts. What were

called roram hats, being fur faced upon wool felts, came into use

directly after the peace, and excited much surprise as to the inven-

tion. Gentlemen's hats, of entire beaver, universally cost eight

dollars.

The use of lace veils to ladies faces is but a modern fashion, not

of more than twenty to thirty years standing. Now they wear black,

white, and-green,&emdash;the last only lately introduced as a summer

veil. In olden time, none wore a veil but as a mark and badge

of mourning, and then, as now, of crape, in preference to lace.

Ancient ladies remembered a time in their early life, when the

ladies wore blue stockings and party-coloured clocks of very stri-

king appearance. May not that fashion, as an extreme ton of the

upper circle in life, explain the adoption of the term, " Blue stock-

ing Club?" I have seen with Samuel Coates, Esq. the wedding

silk stockings of his grandmother, of a lively green and great red

clocks. My grandmother wore in winter very fine worsted green

stockings with a gay clock surmounted with a bunch of tulips.

The late President, Thomas Jefferson, when in Philadelphia, on

his first mission abroad, was dressed in the garb of his day after

this manner, to wit: He wore a long waisted white cloth coat,

scarlet breeches and vest, a cocked hat, shoes and buckles, and

white silk hose.

When President Hancock first came to Philadelphia as president

of the first Congress, he wore a scarlet coat and cocked hat with a

black cockade.

Even spectacles, permanently useful as they are, have been sub-

jected to the caprice of fashion. Now they are occasionally seen

of gold&emdash;a thing I never saw in my youth; neither did I ever see

one young man with spectacles&emdash;now so numerous ! A purblind or

half-sighted youth then deemed it his positive disparagement to be

so regarded. Such would have rather run against a street post six

times a day, than have been seen with them ! Indeed, in early olden

time they had not the art of using temple spectacles. Old Mrs.

Shoemaker, who died in 1825 at the age of 95, said that she had

lived many years in Philadelphia before she ever saw temple spec-

tacles&emdash;a name then given as a new discovery, but now so common

as to have lost its distinctive character. In her early years the

only spectacles she ever saw were called "bridge spectacles,"

without any side supporters, and held on the nose solely by nipping

the bridge of the nose.

My grandmother wore a black velvet mask in winter with a

silver mouth-piece to keep it on, by retaining it in the mouth. I

have been told that green ones have been used in summer for some

few ladies, for riding in the sun on horseback.

Ladies formerly wore cloaks as their chief over-coats; they

were used with some changes of form under the successive names

of roquelaus, capuchins, and cardinals.

In Mrs. Shoemaker's time, above named, they had no knowledge

of umbrellas to keep off rain, but she had seen some few use kiti-

sols-an article as small as present parasols now. They were en-

tirey to keep off rain from ladies. They were of oiled muslin, and

were of various colours from India by way of England. They must,

however,have been but rare, as they never appear in any

advertisements.

Doctor Chanceller and the Rev. Mr. Duche were the first per-

sons in Philadelphia who were ever seen to wear umbrellas to keep

off the rain. They were of oiled linen, very coarse and clumsy,

with ratan sticks. Before their time, some doctors and ministers

used an oiled linen cape hooked round their shoulders, looking not

unlike the big coat-capes now in use, and then called a roquelaue.

It was only used for severe storms.

About the year 1771, the first efforts were made in Philadelphia

to introduce the use of umbrellas in summer as a defence from the

sun. They were then scouted in the public Gazettes as a ridicu-

lous effeminacy. On the other hand, the physicians recommended

them to keep off vertigoes, epilepsies, sore eyes, fevers, &c. Finally,

as the doctors were their chief patrons, Doctor Chanceller and

Doctor Morgan, with the Rev. Parson Duche, were the first per-

sons who had the hardihood to be so singular as to wear umbrellas

in sun-shine. Mr. Bingham, when he returned from the West

Indies, where he had amassed a great fortune in the Revolution,

appeared abroad in the streets attended by a mulatto boy bearing

his umbrella.

But his example did not take, and he desisted from its use.

In the old time, shagreen-cased watches, of turtle shell and

pinchbeck, were the earliest kind seen; but watches of any kind

were much more rare then. When they began to come into

use, they were so far deemed a matter of pride and show, that men

are living who have heard public Friends express their concern at

seeing their youth in the show of watches or watch chains. It was

so rare to find watches in common use that it was quite an annoy-

ance at the watch makers to be so repeatedly called on by street-

passengers for the hour of the day. Mr. Duffield, therefore, first

set up an out-door clock to give the time of day to people in the

street. Gold chains would have been a wonder then; silver and

steel chains and seals were the mode, and regarded good enough.

The best gentlemen of the country were content with silver watches,

although gold ones were occasionally used. Gold watches for la-

dies was a rare occurrence, and when worn were kept without

display for domestic use.

The men of former days never saw such things as our

Mahomedan whiskers on Christian men.

The use of boots have come in since the war of Independence;

they were first with black tops, after the military, strapped up in

union with the knee bands, afterwards bright tops were intro-

duced. The leggings to these latter were made of buckskin, for

some extreme beaux, for the sake of close fitting a well turned leg.

It having been the object of these pages to notice the change of

fashions in the habiliments of men and women from the olden to

the modern time, it may be necessary to say, that no attempt has

been made to note the quick succession of modern changes, pre-

cisely because they are too rapid and evanescent for any useful

record. The subject, however, leads me to the general remark,

that the general character of our dress is always ill adapted to our

climate; and this fact arises from our national predilection as

English. As English colonists we early introduced the modes of

our British ancestors. They derived their notions of dress from

France; and we, even now, take all annual fashions from the ton

of England,&emdash;a circumstance which leads us into many unseason-

able and injurious imitations, very ill adapted to either our hotter

or colder climate. Here we have the extremes of heat and cold.

There they are moderate. The loose and light habits of the East,

or of southern Europe, would be better adapted to the ardour of

our mid-summers; and the close and warm apparel of the north of

Europe might furnish us better examples for our severe winters.

But in these matters (while enduring the profuse sweating of

90 degrees of heat) we fashion after the modes of England, which

are adapted to a climate of but 70 degrees ! Instead, therefore, of

the broad slouched hat of southern Europe, we have the narrow

brim, a stiff stock or starched-buckram collar for the neck, a coat

so close and tight as if glued to our skins, and boots so closely

set over our insteps and ancles, as if over the lasts on which they

were made ! Our ladies have as many ill adapted dresses and hats,

and sadly their healths are impaired in our rigorous winters, by

their thin stuff-shoes and transparent and light draperies,

affording but slight defence for tender frames against the cold.

The above text was digitally photographed one fragile page at a time. The images were then enhanced and

processed through OCR software to create the text.

Special thanks to my wife Karen whose patience in checking that the text matched the volume

and fixing what the computer could not figure out, was greatly appreciated.

And special thanks to my good friend Mr. Norman Brauer

for the loan of the volume and the ability to use his library's resources.

Made on a MAC

J.W.F.